The "invisible" children of Cobán, Guatemala

- Category: Director Blogs

- Hits: 311

Sunday, 25th of January, 2026

Cobán is tucked into the green highlands of Alta Verapaz and feels a world away from the noise of Guatemala City. The air is cooler here, the clouds hang low, and the streets move at a gentler pace. The surrounding hills remind me of Germany and Switzerland, and their likeness to Europe was one of the reasons many Germans settled here in the late 19th Century, establishing businesses and creating an intriguing fusion of Guatemalan and German culture.

But as is so often the case, the serenity of this city, cradled in misty mountains, does not tell the whole story.

This past week, I came to Cobán to continue the mapping of street-living and street-connected children, work that requires time, listening, and presence. Unlike larger cities, the vulnerability here is quieter and more dispersed. Children are less visible, less obvious, and often woven into informal work, family breakdown, migration routes, and hidden urban poverty. You don’t “find” them by accident. You have to walk, observe, talk, and earn trust.

Mapping isn’t about numbers alone. It’s about understanding where children gather, why they are there, and what risks surround them. It’s about noticing the boy who drifts around the market all day but never seems to go home; the girl selling small items on the pavement long after school hours; the group of young people who sleep somewhere nearby but remain invisible during the day.

Cobán once again reminded me why this work matters so deeply. Because even in places wrapped in beauty, children can grow up believing that hope isn’t meant for them. And yet, with the right intervention at the right time, even the smallest glimmer can become a turning point.

This week was about listening to the city and to children whose stories are so easily missed. It was an intense and exciting time of wandering the city centre, meeting people whose experiences and memories no one had taken the time to truly listen to or record.

My time on the streets is always an initial burst of information overload. I was joined by Sandy, an old friend who worked alongside me on the streets of Guatemala City 12 years ago and who, together with her husband and three children, now lives, works, and ministers in San Juan Chamelco, a small town just 15 minutes from Cobán.

Despite living here for nearly ten years, Sandy was keen to walk the city streets with me, listening to the voices of those who call the streets home and to those whose connection to street life remains strong.

I wasn’t expecting to receive so much insight in such a short period of time. We listened to Andrés, a 65-year-old man who has been cleaning shoes in the city park for 52 years. His experience was invaluable, offering a window into the past that confirmed many of my observations about street-living children.

In the early 1990s, the number of street-living children in Guatemala rose to an estimated 5,000 (Casa Alianza and the BBC), with the majority surviving on the streets of Guatemala City. Sitting on the low, crumbling concrete wall where his customers rest while Andrés polishes their shoes, he told us about the 30 to 50 street-living children once present in Cobán, and how those numbers gradually reduced through the intervention of local charities, churches, and the development of state institutions that began offering children alternatives to life on the streets.

His memories were later confirmed and expanded through conversations with local police, municipal authorities, and charity practitioners, including Odethe, who has supported children in the city for more than 30 years.

The situation today is starkly different and helps explain both how and why the number of street-living children here has fallen, now effectively down to zero.

I still have two more major cities to visit in Guatemala before my studies take me to Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. I’m quietly encouraged to see that what has been achieved in Guatemala City has also been realised in Cobán, something I also witnessed earlier this year in Belize.

Yet as we continued walking and listening, another reality emerged. Conversations with people across the city revealed how urgently the hidden risks facing children must still be confronted.

We met Osman, a 12-year-old boy who, alongside his nine-year-old sister, spends his days wandering the city streets selling sweets. Their small hands clutch a small cardboard tray of sweets, and with them, a constant battle, not just to earn enough, but to resist the hunger that tempts them to eat what they are meant to sell.

Osman embodies what it means to have a strong connection to the streets: too young to carry such responsibility yet already navigating survival with quiet determination. The streets are not just a workplace for him; they are shaping his childhood, his choices, and his future.

Recognising the risks he faces, Sandy and her husband, Josué, have committed to following up with Osman and his family next week, a first step towards ensuring that this moment of encounter becomes the beginning of something safer, more hopeful, and more permanent.

As the mapping progressed, the data told a far darker story than the quiet streets suggest. I discovered that girls as young as nine years old are dying in childbirth, not through accident or illness, but as a direct result of sexual abuse by family members. The prevalence of these cases here is more than twice the national average, exposing a level of harm that remains largely unseen, unspoken, and unchallenged.

These are not anomalies. They are the consequences of silence, stigma, and systems that fail to intervene early enough. When abuse is hidden within families, girls become trapped in cycles of violence with devastating, and sometimes fatal, outcomes.

As we continue to reach the most vulnerable children, we will need more resources, more volunteers, and far more time to listen to those who understand this reality best - the children themselves.

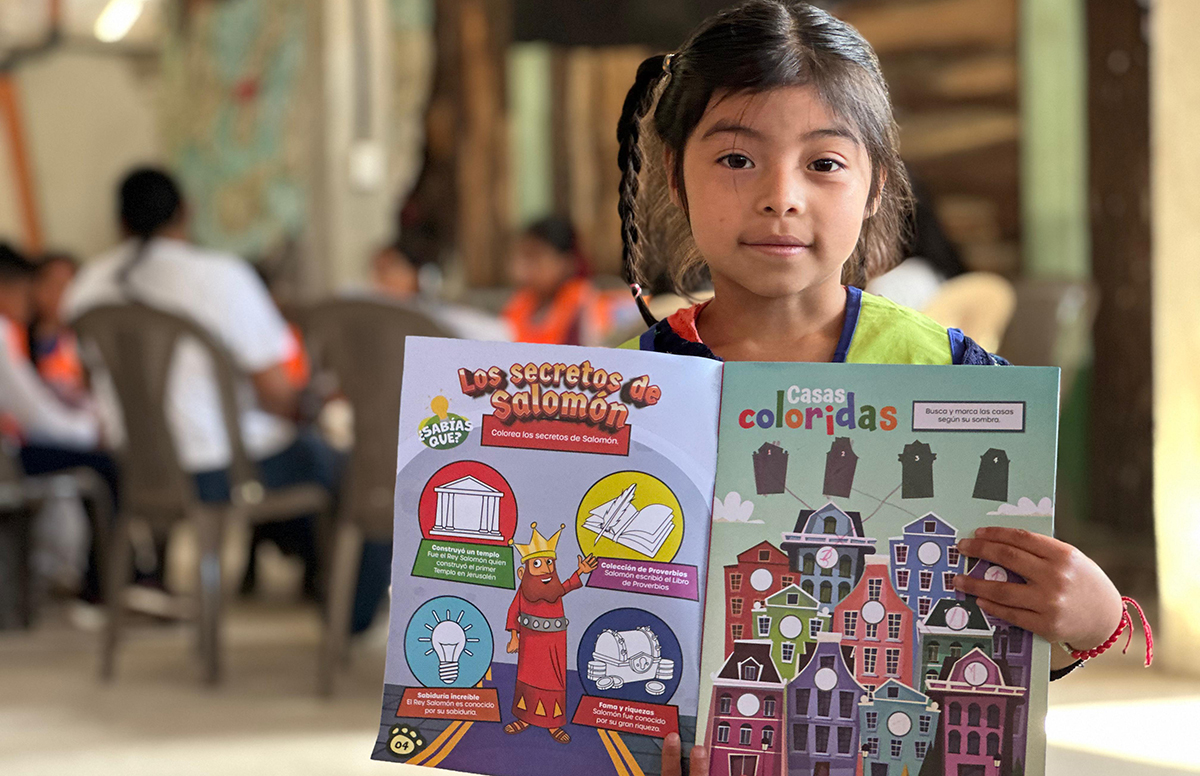

To finish the week, Sandy invited me to visit a small Christian children’s club that she and her husband, Josué, run in a town just outside Cobán. The contrast could not have been more striking.

Around 80 children, aged five to twelve, gathered that morning. Laughter filled the space almost immediately. Games helped break the ice, songs were sung with the kind of enthusiasm only children can muster, and Bible stories were shared in ways that felt joyful, accessible, and alive. For a few hours, their large garage became a place of safety, fun, and belonging.

What stayed with me most was not the programme itself, but what it represented. In a region where so many children experience neglect, abuse, and invisibility, this simple club offered something profoundly powerful: attention, care, and consistent love. Each child was known by name. Each one was welcomed without condition. And each one was fascinated by a tall Englishman who had come to listen and to learn.

It was a reminder that prevention doesn’t always begin with large systems or complex interventions. Sometimes it starts with a safe space, a trusted adult, and a message repeated week after week: every child has value, dignity, and hope. In places where the risks are hidden, and the need is great, moments like these matter more than we often realise.

Duncan Dyason is the founder and Director of Street Kids Direct and founder of TOYBOX UK, El Castillo in Guatemala and SKDGuatemala. He first started working with street children in 1992, when he moved to Guatemala City after watching the harrowing BBC documentary "They Shoot Children Don´t They?" His work has been honoured by Her Majesty the Queen, and he was awarded an MBE in the year he celebrated having worked for over 25 years to reduce the number of children on the streets from 5,000 to zero. Duncan continues to live and volunteer with the Street Kids Direct charity in Guatemala City.

Duncan Dyason is the founder and Director of Street Kids Direct and founder of TOYBOX UK, El Castillo in Guatemala and SKDGuatemala. He first started working with street children in 1992, when he moved to Guatemala City after watching the harrowing BBC documentary "They Shoot Children Don´t They?" His work has been honoured by Her Majesty the Queen, and he was awarded an MBE in the year he celebrated having worked for over 25 years to reduce the number of children on the streets from 5,000 to zero. Duncan continues to live and volunteer with the Street Kids Direct charity in Guatemala City.

It’s not just their story; it’s Honduras’ story. The World Bank reports that nearly 8 in 10 children of late primary age in Honduras lack proficiency in reading skills. Imagine sitting through years of lessons and still being unable to understand a sentence. This occurs every day. Although 95% of children enrol in primary school, the reality is grim: only 6 out of every 20 will graduate from secondary school. By adolescence, almost 41% of boys aged 12–16 are already out of school.

It’s not just their story; it’s Honduras’ story. The World Bank reports that nearly 8 in 10 children of late primary age in Honduras lack proficiency in reading skills. Imagine sitting through years of lessons and still being unable to understand a sentence. This occurs every day. Although 95% of children enrol in primary school, the reality is grim: only 6 out of every 20 will graduate from secondary school. By adolescence, almost 41% of boys aged 12–16 are already out of school.